|

|

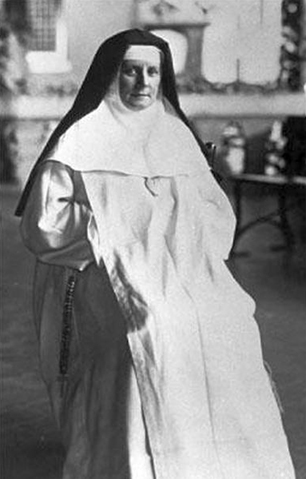

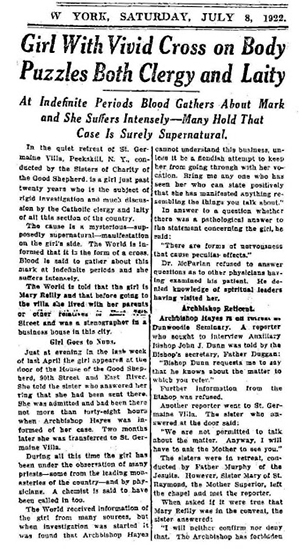

Left image is Sr. Mary of the Crown of Thorns/Margaret Reilly. Right image is a newspaper clipping about the below events. [See/view] larger image of above newspaper clipping. |

Following text from [here]. Sr. Mary of the Crown of Thorns - A Good Shepherd Sister living in Peekskill, NY who was hailed by many as a mystic and stigmatic.

The remarkable true story of Sr. Mary of the Crown of Thorns (born Margaret Reilly, 1884-1937), if authentic, she would be one of the first reported stigmatics in America.

Those who study the lives of mystics and visionaries soon discover that while often a "cult" of avid followers develop around such persons, on the other hand some of their contemporaries often view such persons with excessive skepticism and doubt. For the disciple is not above the Master, one could surmise. And this writer has yet to find a mystic that did not have at least some controversy surrounding them. And so it is also in the life of Margaret Reilly (Sr. Mary of the Crown of Thorns) that we find a life story full of mystical and supernatural mystery, surrounded by strong supporters, including two prominent bishops and a number of priests and religious, yet at the same time also a number of noteworthy detractors.

One thing is for certain: during her lifetime she gained the attention of quite a few people outside of her convent in Peekskill, NY., and after her death in 1937 there was a significant movement pushing for her canonization. Eventually however the cause stalled in the 1960's, lacking the support of the local Archbishop, and also the financial backing and support of her religious Community, the Good Shepherd Sisters. And so it is that today she is almost completely unknown, her life being nearly forgotten.

What precisely happened in the life of this Manhattan Irish woman from a modest family concerning the remarkable mystical gifts purportedly given to her is very much a intriguing mystery to this day. For she was reported to have received the stigmata (the bleeding wounds of Christ), and also a indelible, raised image of a crucifix on her breast, directly over her heart, which reportedly also manifested itself on her bedroom wall in the convent, along with extensive physical torments that seemed to mirror much of the passion of Jesus. These mystical graces and sufferings drew the attention, admiration and cynicism of many persons in New York, and around the country, and her notoriety spanned from 1921 to 1937. This article will attempt to shed some light on her life and the reported supernatural graces given to her.

Early life and first mystical experiences - A raised crucifix on her chest

Margaret Reilly was born in Manhattan, New York on on July 25, 1884, the youngest of 7 children into a poor, Irish family. Her father, Patrick Reilly, was a construction contractor, and her mother, Mary McLoughlin Reilly was a homemaker. Stories of Margaret's childhood reveal a early and intense devotion to Jesus. Margaret preferred her crucifix to a doll and she treated the crucifix like a doll, taking it for walks in her doll buggy, wrapping it to keep Jesus warm, and hugging it close to her at night. When her daughter required discipline, Mrs. Reilly threatened to take away the crucifix as punishment. She preferred being alone instead of playing with other children. As a youngster, Margaret learned of penitential practices, such as putting pebbles in her shoes as a form of sacrifice and self-mortification, which she learned from the Sisters of Charity who staffed her parochial school. Later as a teenager she took to wearing a hair shirt underneath her clothing, as a form or reparation and penance. Eventually however her spiritual director requested that she stop that particular practice.

After making her First Communion, Margaret also secured special permission to receive Communion daily (an exception for young children at that time). This special grace represented some hardship however, as it obliged her to walk ten blocks before breakfast to attend Mass, and then return home for a quick meal before walking to school.Margaret also developed a fondness for the Stations of the Cross, reportedly praying the stations three times in one day, until one of her older sisters told her to stop.

The first evidence of mysticism is reported in November 1913, when at age 29 she states that a two-inch-long red cross had appeared on her breast. On that day, she recalled:

“It pleased our dear Lord to send me a very severe illness for which He prepared me in a most extraordinary way. In my illness, I beheld our dear L. (Lord) nailed to the Cross and covered with Wounds…. ‘Thorn,’ He called me; ‘upon thy breast I place a Cross.’ My eyes raised above. He smiled and spoke: ‘Take thou this Cross because 'tis Thorn I love.’ Then a sharp pain … when suddenly my eyes closed to all around me. My very soul became entirely rapt and absorbed in the contemplation of the Most Holy Trinity.”

And four years later in 1917 she reports another mystical grace. She relates that while stooping over the oven to prepare a fish supper with her mother, she felt a sharp pain over her heart, and saw a three-dimensional crucifix emerging in blood. Her mother quickly put her to bed and immediately telephoned their pastor. The crucifix reportedly remained visible until December 8, 1917. In a friend's recollection, the mark resembled a “raised, sunburned area,” red in color, approximately two inches long. At times the three-dimensional corpus even changed color, for according to one chronicler, “Sometimes it was red, sometimes purple, sometimes livid." Jesus reportedly revealed to Margaret whom He called "Little Thorn" the meaning of the changing of colors; they meant to reveal the sufferings of His Church in various ways.

First report of the stigmata and the crown of thorns, along with a second appearance of the the raised crucifix over her heart. She becomes a religious sister.

In September of 1921, Margaret made a extended spiritual retreat at Mount St. Florence convent in Peekskill, NY. It appears that this retreat was actually more of a postulancy for her to see if she was called to the religious life of the Good Shepherd sisters. On the fourth morning of the retreat, Margaret took a stroll to view a statue of the Sacred Heart of Jesus on the convent grounds. As she returned to her room to lie down, she claims to have had a vision of Jesus standing at the foot of the bed.

He reportedly said, “I give you my cross upon your breast, because I love you very much; and you are to suffer for My very own.” And Jesus explained that “my very own” in this case referred to priests and nuns.

At this time, the same image from her chest was miraculously duplicated on the wall of the room that she was staying in. About three inches in length, it was first documented by the superior of the convent, Mother Raymond (Born Bridget Cahill in Worcester, Massachusetts) who was further surprised to find that Margaret's left side and feet were now bleeding. Mother Raymond reported to one of Margaret's cousins, who was also a nun: “She has shown me her beautiful Cross and you may feel certain that she was most welcome (here).”

Even before Margaret's arrival at Peekskill, Mother Raymond claimed to have witnessed (although she does not specify where) the perfectly formed cross and corpus with its feet resting on Margaret's heart, “at times diffused with blood.”

For the next 33 days—each day, as the superior believed, symbolizing a year of Jesus's life—Margaret remained bedridden at the convent in acute pain and bleeding profusely from four wound sites in her hands and feet. Jesus told Margaret that the foot wounds were the beginning of her complete stigmatization. Puncture wounds appeared around her forehead as well, as though from a wreath of thorns. In a vision, Jesus told her that she would now be named “Thorn.” reportedly stating: “Now you are my Thorn, but soon you shall be my Lily of Delight.”

Later, the stigmata would intensify from Wednesday through Friday each week. Returning to the story of her visit and entering the convent, on November 11, 1921 her face was said to be marked as though by whips. Margaret said she could feel the separate lashes as they were given on her face, also when they were given on her whole body. These lashes were reportedly sometimes inflicted by our Lord Himself, or by St. Michael or by her Guardian Angel. Margaret could even see this instrument: the discipline contained 48 strips of fine steel with thorn-like projections. There was also a piece of lead 2¾ inches long attached to the center ring.

Mother Raymond reported that among Margaret's wounds, the scourge marks were “more painful than the wounds of the hands and feet and side. The pain in the chest is as if an army of people were kneeling on the chest.”

The cross impressed on the skin over Margaret's heart that began this chain of events disappeared entirely from her body around December 15, 1921.

Except for a couple of visits to relatives, Margaret remained in the convent during her "probationary" or discernment period, and on December 8, 1923, the Feast of the Immaculate Conception, was finally able to make her preliminary vows as a Good Shepherd sister, taking the name "Sister Mary of the Crown of Thorns", a name which was reportedly given to her by Jesus. It should be noted here however that she was delayed in making this religious profession due to the fact that a few of the Good Shepherd nuns in the Community had doubts concerning her purported mystical gifts.

A description of the crucifix imprinted upon the wall in Sr. Thorn's room

Sr. Thorn had a cousin named Sr. Sebastian, a Dominican nun living in Ohio. On August 25, 1922, Sister Sebastian traveled to Peekskill to observe things firsthand, accompanied by Sr. Thorn's brother Tom. Prior to this visit Sr. Catherine had already received some photographs or drawings of the mark on her cousin's skin from Mother Raymond, who concluded her letter with the entreaty: “Trusting, dear Sister, this will somewhat satisfy your interest, asking a little prayer, and begging to accept the enclosed pictures which are a true copy of the Cross and position on her breast.”

Normally visitors were forbidden to see her bedroom with the alleged miraculous cross on the wall under orders from the congregation's appointed confessor, Father John F. Brady, but on this occasion permission was given. Sr Sebastian found the room “...small and very plain. I first looked at the miraculous Crucifix (on the wall). It is much like the one on the picture, and about that size. I could see the Face of our Lord, and the lettering is also very plain. We used a magnifying glass. From where I stood I kissed the feet, but would have to stand on something to reach the Face.”

Of this particular visit Sr Sebastian stated that the crucifix was not apparent on her cousin's chest at that time, but that she experienced the pain of invisible stigmata there and in her hands, feet, and side. Sr Sebastian's impression of Margaret was of “...the dearest, sweetest soul, and heavenly in appearance, but as simple and as natural as a child.”

But going back to the crucifix imprinted upon the wall in her bedroom, Paula M. Kane notes in her book that "All accounts agreed that efforts to remove the image from the wall proved to be futile, even when scraped."

Sr Thorn is confined to a wheelchair

On the very day that the provincial was to accompany Margaret from Peekskill to Manhattan to begin her official novitiate, Margaret suddenly lost the use of her legs, and never walked again. As Mother Raymond recorded, Margaret had returned to her cell after Mass in the morning and sat down. Her limbs grew stiff and she became unable to walk. She was carried to her bed. Mother Raymond later stated that God had forewarned Margaret that she was to remain there because “..the novitiate would come to Peekskill to her.”

Along with Sr. Thorn's recent immobility there was also added the special care required by her stigmata. Benedict Bradley, a Benedictine monk in New Jersey who visited Peekskill in November and December 1922, verified that Margaret was mostly bedridden. When she left her bed for chapel and meals, she moved about by crawling on her hands and knees. Her spiritual director forbade her from doing even this after she reported that Satan had thrown her down the stairs repeatedly, and he purportedly filled her tunic with pins to prevent her from climbing the stairs on her knees. Thus the sisters were now required to lift Margaret out of her wheelchair and carry her up and down stairs. This partial paralysis also prevented Margaret from performing the usual convent chores undertaken by every sister. Consequently, when she was permitted to remain at Peekskill, she was assigned to work the telephone switchboard.

Attacks from the demons

On December 9,1921, the day after she received her first veil as a postulant, Sr. Thorn faced a demonic attack. “As she was eating her supper,” wrote a sister named Carmelita, “her plate was broken, coffee spilt on the bed and she was pulled and dragged around for sometime.” Later that night, (Dec. 9), Sr. Thorn asked Mother Raymond to stay with her and not let the “evil one” tempt her “..with some evil suggestions he was making.”

Sr. Carmelita also wrote “Margaret had complained of noises in her room at night, but it was attributed to other causes.” Early on, most of the unusual activity continued to involve ordinary household objects: the turpentine bottle left in Margaret's cell by Dr. McParlan was broken, flower vases were overturned, liquids were spilled, china was cracked, a holy-water font was broken, embroidery was burned, dress buttons were removed, and the glass on a picture of the Infant Jesus was shattered. “For some days,” Mother Raymond also recalled, “the whole house smelt of sulfur.”

Margaret often endured taunts from the demons, who showed her “awful pictures” and “impure sights” that she declared were “far more painful to her than the beatings.” Add to this, Satan often assumed the appearance of Jesus in an attempt to fool Margaret.

Mother Raymond left numerous notes stating: “One attack at Holy Communion as usual.” On another occasion she wrote: “Margaret sustained an awful attack after holy Communion near the confessional. Satan threw her down, tore off her postulant's cuffs, threw her shawl over the head of Sr. Mary of St. Luthgarde, seemingly to blind them so they could not protect Margaret; pulled feet to break them; slapped her face so it could be heard; jerked her and dragged her, then left her.”

According to Sr. Thorn, the demons took on the forms of a black cat, a rat, a seal, slime, and both handsome and ugly men. During the summer of 1922, Mother Raymond temporarily left Margaret, and when she returned, she found Margaret on the floor next to the telephone switchboard. The switchboard had been overturned on St Thorn's head, leaving a lump over her eye and knocking plaster out of the wall. Mother Raymond was so embarrassed when the electrician commented on the extensive damage that when another incident smashed windowpanes and bookcase glass, she was reluctant to contact a repairman for fear that outsiders would think that the convent was a “roughhouse.”

Yet another violent episode reportedly occurred during Mass on November 21,1923, while the sisters were listening to the final portion of the Eucharistic prayer, Sr Thorn was thrown from her wheelchair to the floor and her head was jammed under the radiator. Yet, for all of its strangeness, this diabolical activity had usefulness beyond their convent in redeeming sinners, for even as Margaret struggled with a demon who knocked her down and twisted her leg around a chair, Saint Colette allegedly appeared to her and reassured her in a vision that “a certain soul has been saved through your struggles.”

Visiting Peekskill from Missouri, Sister Carmelita Quinn recorded an episode on February 17, 1922:

“Breakfast and dinner were spoiled, it meant that Margaret Reilly thought the food had a bad taste and smell. Often, Margaret envisioned little black bugs on the food and bread that repelled her from eating.” In a vision years later, the Virgin Mary comforted Sister Thorn and told her that the evil spirits would no longer be permitted to assault her.

More notes on her alleged stigmata

Sr. Thorn believed that she suffered as a victim soul for the conversion and salvation of souls. She attributed the pain in the location of her stigmatic wounds with specific intentions: pain in her left foot indicated prayers for Archbishop Hayes and the pope; pain in her right foot meant prayers for priests; her left hand was dedicated to laypeople praying to her; and her right hand was to atone for nuns seeking higher education who forgot their duty by seeking worldly advantages. Finally, Margaret's heart symbolized the Good Shepherds and “another convent dear to Jesus.” Sister Thorn claimed that the scourge marks on her thighs and the crown of thorns on her forehead were offered for priests who were offending Jesus. She endured these torments to fulfill God's special mission for her to obtain grace for others, especially for priests and religious.

Add to this the fact that some of Sr. Thorn's devotees spent their time trying to ascertain the meaning of the changing colors of the corpus on the crucifix upon her chest and also her bedroom wall, revealing a obvious determination to affirm the bond between suffering and the possible sanctity in her life.

It is interesting to note also that in her book "Sister Thorn and Catholic Mysticism in Modern America" Paula M Kane points out that it seems that Sr. Thorn's stigmata were mostly invisible in nature. According to her readings, Sr. Thorn's visible, bloodied stigmata seemingly lasted only ten weeks, from September 4 to November 18, 1921.

Fame and opposition

Those outside of the convent first learned of "the bleeding nun at Peekskill" through a letter written by a Passionist priest named Father Bertrand Barry who composed a sort of “spiritual chain letter” in early 1922 that he sent to numerous friends. It became an embarrassment to the Good Shepherd Sisters because it contained many errors, and drew unwanted attention to the religious order, but its odd details excited the public and drew fervent crowds to the convent.

On Saturday, July 8, 1922, "The New York World" newspaper ran the headlines "Girl with Vivid Cross on Body Puzzles Both Clergy and Laity. At Indefinite Periods Blood Gathers about Mark and She Suffers Intensely—Many Hold That Case Is Surely Supernatural". One should note however that this article actually contained several errors.

Stories and rumors concerning Sr. Thorn abounded amongst both religious and laity. Many who knew her either as a child or young adult were positive towards her. The superior of the Community, Mother Raymond, who spent the most time each day with Sr Thorn, was a strong supporter. Yet she became aware that at least a few of the Sisters in the Community were displeased with Sr. Thorn, so as time progressed, Mother Raymond decided to have a private written census of each of the Sisters in the convent. The record shows that the majority of them were supportive of Sr. Thorn, but several were in opposition, for various reasons. Of the approximately 50 professed and "lay" Sisters associated with the convent, there were six Sisters who were either "not satisfied" or "not contented" with Sr. Thorn. As side note, interestingly it seems that most of the Sisters in the convent at this point had not actually seen Sr. Thorns stigmata, which leads one to conclude that they likely were only visible for a short period(s) of time, and like other stigmatics it is quite possible that they came and went and/or were not visible at times.

Archbishop Patrick Hayes of New York oversaw the official investigation of Sister Thorn, which began some three years before he was named a cardinal. The medical part of the investigation consisted of evaluations from three separate physicians--together Dr. James J. Walsh, and Dr John B. Lynch felt that Margaret's "medical symptoms" were attributed to a "nervous condition" and possible "hysteria." On the other hand, Dr. Thomas F. McParlan became convinced that her various medical conditions were not attributable to natural origins or any ordinary means, and he eventually became one of Sr. Thorns prominent supporters.

For his part, over the years he was publicly cautious concerning Sr. Thorn, and until his death which occurred one year after hers he remained essentially neutral concerning her. One could assume that if his investigation had found anything significantly wrong he presumably would have sanctioned Sr. Thorn in various ways.

As for religious outside the convent, there was a New York Jesuit, Fr. James McGivney, who wrote a private letter to another Jesuit, Fr. Herbert Thurston, expressing his deep concern regarding St Thorn. Fr. James McGivney had given a couple of retreats at the Peeskill convent, where he presumably obtained various information concerning Sr Thorn.

For his part, Fr. Herbert Thurston SJ, a very popular scholar known for his books on mysticism, occult phenomena, and parapsychology, was a significant supporter of Sr. Thorn. In 1925 he published a study of Margaret Reilly, whom he concealed as “Kate Ryan,” for an article in the British Catholic journal "The Month." Also around that time, Fr. Thurston was rumored to be one of four Vatican consultors for the Reilly case. Father Lucas Etlin was another priest who was very supportive of Sr. Thorn.

However, As Paula M. Kane points out in her excellent book, regardless of what those in favor of Sr. Thorn believed, certain pieces of evidence point to her purported stigmata as possibly being a fraudulent: from her sudden paralysis on the very day she was being asked to leave the convent; the short duration of the bleeding wounds and the lack of witnesses to and physical evidence of their onset; the controversial crucifix image on her chest and wall that closely resembled a commercial stamp at that time; the confusion in the written record regarding the timing, location, and appearance of her various physical markings; and the many poltergeist incidents at the convent that she herself could have performed.

On the other hand, testimonies supporting her authenticity came from trustworthy eyewitnesses who beheld and nursed her wounds, along with from the affirmations of Sister Carmelita Quinn, Dr. McParlan and Cardinal James McIntyre, the longtime conservative Archbishop of Los Angeles. The latter's association with Sr. Margaret can be understood when looking at the historical record. James McIntyre was ordained by Archbishop Patrick Hayes of New York (Sr. Thorn's bishop) in 1921, and two years later he was appointed chancellor of the Archdiocese--a position he held for 11 years until 1934--and it was in this position that he was able to keep very close tabs on the situation concerning Sr. Thorn.

In 1940, McIntyre was appointed Auxiliary Bishop of New York and it is during this time in particular that he became known for his support for Sr. Thorn. Later, when he became archbishop of Los Angeles, he continued to campaign on behalf of Sister Thorn. He gave the Good Shepherds in California his only photograph of her in order to convince them “that while the religious of her own Congregation did not all approve or believe in her saintliness, that there were others who did.”. He also gave a rosary to the superior, telling her: “Do not let anyone deprive you of the privilege of having a Saint in your congregation."

Her numerous illnesses and death

Starting with the critical moments in December 1923 when a weakened Margaret was suffering intensely, the sisters had everything in readiness for what they thought might be her death bed Profession. Yet, she clung to life. In January 1924 Margaret was about to receive the last rites, yet she rallied once more. In February Archbishop Patrick Hayes visited the convent, reporting that he scarcely recognized her since “she looks so very frail as if the lamp was nearly burned out.” At the close of 1924, she was still “suffering greatly and growing weaker.” In May 1925 she was frailer still and “suffering very much,” and by December she seemed “supremely happy” although in great pain. In 1926 Margaret “suffered a great deal during Lent” and during that summer was disturbed by constant vomiting. “There are days when one wonders how she lives,” remarked Mother St. Francis Xavier Hickey. In 1927 it was noted that her “spine was attacked now as well as the pancreas. The pain in her head is awful at times.” That year, Dr. Thomas McParlan reported on Margaret's new set of ailments: “Yesterday I saw Sister Thorn. The mass in her abdomen which includes the pancreas is greatly enlarged and her sufferings are terrible. There is no position that gives her the faintest relief and she looks very badly. I am greatly worried over her condition and feel so powerless to anything for her.” By August, Mother Hickey (who by that time had replaced Mother Raymond) feared “poor little Sister cannot last much longer. She is suffering so much, but always so sweetly and patiently.”

Nevertheless, despite her declining health, Margaret survived for another decade. Most of those associated wither her believed that her illnesses were primarily supernaturally induced, meaning that her suffering was God's will in that it was for reparation and for the conversion of sinners.

“Our Lord is going to give us an Irish American saint!” her bishop, Archbishop Patrick Hayes, reportedly said with enthusiasm to Father Lucas Etlin, an avid supporter of Sr. Thorn.

Yet the archbishop and many others closely connected to Sister Thorn refused to give her case any significant public support, and after her death her cause for beatification eventually faltered in the 1960's.

After a life of suffering and sacrifice, Sr. Mary Crown of Thorns (Margaret Reilly) died at age 52 in May 18, 1937. When Sister Thorn finally died, she was attended by the two women closest to her, Mother Raymond and Sister Carmelita. Mother Raymond had left Sr. Thorn's room for two minutes to fetch a drink of water; when she returned, she found Margaret vomiting blood into the basin on her table. Sister Thorn died soon afterward.

Mother Raymond was crushed by the loss of her dearest friend. She wrote a letter in her own hand to Mother Dolorosa at the Benedictine convent in Clyde, Missouri, describing how Sr. Thorn had suffered heroically "...thru her ulcers, pancreas and other ills. Then the attacks of the evil one, her sweet pains ( her stigmata). Some tests confirmed cancer of all the left side, also the bladder; she refused opiates, wanting to be coherent to make a good confession before communion. I will miss her yes more than I can say but I am grateful He took her first.Memories crowd in daily and I thank Him for all He did for her and for me."

Sr. Margaret Reilly, pray for us!

"We cannot change the world, taking out all its thorns, making its tasks easy and its burden light; changing all its discord into harmonies, transforming its ugliness into beauty. But we can have our own heart renewed by the grace of God, and thus the world will be made over for us. . . . A soul of song will find sweet music everywhere." — Message from Jesus to Sr. Mary Crown of Thorns